It’s hard to fathom how miserable life in immigrant detention facilities in CA are that detainees are begging to be deported. Parallels abound when thinking about the current treatment of undocumented immigrants caged in pursuit of deportation, and the treatment of Chinese immigrants at Angel Island in the twentieth century. Immigration control and crime and punishment have always been linked in racialized ways that underscore a fundamental mission: deeming certain groups of people unworthy of freedom.

A journey to the Guardian of the Western Gate

In thinking about the contours of immigrant detention and deportation in CA, no site embodies the early era of immigration control in CA like Angel island in the San Francisco Bay. From 1910 to 1940, the United States operated an immigration station on the island that processed nearly a million immigrants from more than 80 countries. European immigrants faced a simple screening and were detained infrequently. Chinese immigrants, subject to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, were detained anywhere from 90 days to 20 months while their applications were considered. Many Chinese detainees expressed their anxiety and despair by writing and carving on the wooden barrack walls. (some poems are still legible today).

Immigration detention is often overlooked as a pillar of the nation’s carceral archipelago. This omission is rooted in a decision made over a century ago by the Supreme Court that determined human confinement in the pursuit of deportation is ‘not imprisonment in a legal sense.’ Immigrant detention operates, in a legal sense, separate and apart from imprisonment but fills jails, prisons, and detention facilities across the country. Angel island, across the Bay from San Quentin State Prison, played a major role in the settlement of the West — but did so while caging immigrants in a “legal” manner.

Private prisons in CA *don’t* provide adequate healthcare for inmates

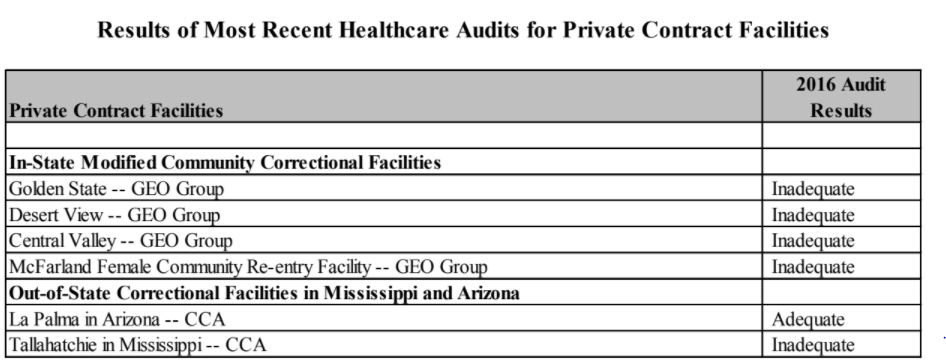

A recent inquiry has found that 5 of the 6 private prisons that CA contracts out to failed to provide adequate medical care for inmates in 2016.

The audit findings include patients not being seen in a timely manner, patients not receiving their medications as required, and failing to properly dispose of used needles. In several facilities, nurses didn’t refer patients to a physician. In some instances, nurses didn’t confirm the identity of an individual before administering medications.

This is problematic, folks. Follow the layers: The Supreme Court mandated CA to reduce prison overcrowding in order to provide better healthcare to inmates. CA responded by shipping non-violent, non-serious, and non-sexual offenders to county jails to alleviate overcrowding, but these facilities don’t have expansive medical units because they are designed for temporary housing. One of CA’s other responses was to rely more on private prisons to warehouse inmates, facilities which — you guessed it — fail to provide adequate healthcare. Ostensibly CA is committed to providing healthcare to inmates, but empirical trends paint a different picture.

CA’s crime rate has reached its lowest rate in 47 years

According to the CA Attorney General’s Open Justice Database, nearly every category of crime in CA has decreased substantially across the board. Violent and property offenses, which account for the majority of CA prisoners, has decreased in both overall number and rate per population. CA’s property crime rate (burglary, motor vehicle theft, and larceny-theft) declined dramatically between 1982-2014 for each offense. Burglary decreased by 74%, motor vehicle theft by 41%, and larceny-theft by 59%. Since 1980, CA has also experienced a dramatic decrease in its violent crime rate (homicide, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault). In comparing 1982 to 2014, rates for homicide decreased by 61%, rape by 52%, robbery by 66%, and aggravated assault by 37%.

In 2015, the arrest rate in California overall was 4.4% lower than the arrest rate in 2014. The majority of the decline was due to a 17.1% decline in juvenile arrests. The felony arrest rate decreased by 29%, while the total misdemeanor arrest rate increased by 8.8%. 45.4% of misdemeanor arrests were either alcohol or drug-related. 66.9% of felony arrests resulted in a conviction.

The simple equation that more crime leads to more arrests and thus to more convictions and prisoners is cast in doubt by these recent statistics. Crime is lower than it’s been in nearly half a century, but prison admission rates have not seen a similar drop in response. It’s true that CA prisons have dropped from a peak of 173,000 inmates in 2007 to 118,560 in 2017, but this is due to Realignment, changes to the Three Strikes law, and Prop 47 (with Prop 57 soon to contribute to reducing prison populations). These changes have occurred irrespective of falling crime rates.

Prosecutorial behavior is almost impossible to study with any accuracy, but it seems like the logical place to start for trying to unpack this current paradox. Prosecutors are the gatekeepers of prison admissions, but they are directly elected and we’ve seen how politically popular tough on crime rhetoric is. It seems safe to assume that most Californians would be surprised to learn crime is exceptionally low. Media representations of crime are partially to blame, but a larger culture of fear seems particularly onerous in compounding these issues. It’s almost as if CA is governing through crime.

The fork in the road: Reform or Abolition?

How does one grapple with the diverging paths of reform vs. abolition efforts? Reform is clearly needed, but such efforts serve to reinforce and re-legitimize the system as a whole. Abolition is the radical approach, but mass incarceration wouldn’t happen if there were not already a dispensable subclass of society deemed unworthy of freedom. Is there a way to reform a system that relegates large numbers of people from racially oppressed communities to an isolated existence marked by authoritarian regimes and technologies of seclusion that produce severe mental and spiritual instability that doesn’t involve scrapping it entirely?

Reform efforts could potentially remedy a plethora of crucial issues central to mass incarceration, but it seems unlikely that anything short of abolition could correct minority over-representation. Throughout history, crime and punishment has always been married to race. In 1900, the black-white incarceration disparity in America was seven to one — roughly the same disparity that exists today on a national scale. The same regions of the country that employ capital punishment the most frequently today are the same regions that had the greatest concentration of lynchings in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

A serious redesign of our carceral state would start be envisioning a smaller prison population. But to return to pre-1972 levels of incarceration America would have to cut it’s by prison and jail population by nearly 80 percent. The task is Herculean. Such restructuring efforts cannot pretend that the past fifty years of criminal justice policy didn’t inflict nearly-unimaginable mistreatment and damage. We cannot adequately reform the justice system if we refuse to see the interconnectedness to institutions, communities, and the politics that encompass it.

Let’s imagine for a moment the impact of tangible reform efforts such as sentencing re-evaluation or the softening of post-release legal barriers. If crime rates were to swell in this reformist realm, there is no reason to believe that communities of color would not be disproportionately imprisoned again. State sanctioned devastation is generational for communities of color in America — and incarceration is the current mechanism that ensures devastation continues. Incarceration diminishes any hope of upward economic mobility. Incarceration disqualifies one from feeding their family with food stamps. Incarceration allows for housing discrimination based on criminal background checks. Incarceration increases the risk of homelessness and mental health issues. Incarceration increases the chance of being incarcerated again. If generational devastation is the black hole in which communities of color reside, incarceration is the door closing overhead.

Enslavement lasted over 250 years. The next 150 years involved Jim Crow, convict-leasing, and mass incarceration. Perhaps the only response to the State trying to abolish certain communities is abolition in return.